Art's ability to build worlds and destroy them

By Ellen Lee

The year is coming to a close, and the dissociative feeling surrounding every year-end has started creeping in again. The last week of December is a vertiginous time of looking back and brooding on the mysterious nature of time’s passing. Is it possible that we emerged from our longest and most chaotic economic lockdown to date (lasting from May till September? -ish?) only a few months ago when everything seems so normal now? Is it possible that Beeple sold his work for an eight-figure sum in this same year, when it feels like NFTs have been dominating art discourse for so much longer than that?

Come year-end, time and its continuity start to feel like slippery concepts, which sounds scary, but perhaps could also be a good thing. Nothing matters, nothing lasts forever. The tides can change on a whim. Anything and everything is within the realm of possibility.

One of the ways of living forever—of keeping memory indelible—is the blockchain. Non-fungible tokens (NFTs), which utilise blockchain technology, were a major topic this year ever since American artist Beeple sold his NFT work, Everydays: The First 5000 Days, for $69 million.

Red Hong Yi talking about the process of making Doge to the Moon.

In Malaysia, Sabah-born artist Red Hong Yi made waves when she successfully auctioned off her entire Memebank NFT series. Images of the Doge meme spoofed onto a Chinese yuan plastered everyone’s feeds as Doge to the Moon, the most famous of the Memebank series of spoof currencies, sold for approximately 36.3ETH (RM320,000). The sale caused a stir on social media as traditional artists questioned perceived hypocrisy in Red minting NFTs—which notoriously consumes huge amounts of energy—so soon after debuting her TIME Magazine cover on climate change. This was also the year where it became pertinent to distinguish between digital/NFT artists and artists working within the traditional mode (in an NFT age, how do you refer to “traditional” or “old school” artists without making them sound old? Do we call them “fiat artists” now?) as the definitions of art and artistry became muddied.

Red Hong Yi’s lauded TIME Magazine cover.

The rise of NFTs has also helped hasten the decentralisation of the local art scene. For Kuala Lumpur-based artist Visithra Manikam, NFT platforms gave her the power to forge her own path as an artist, outside the supposed elitism of the traditional art market. In an interview with The Vibes, the artist described being sidelined from the art scene due to her race and being treated as a “token Indian” when invited to exhibitions. When Manikam took her work to the OpenSea NFT platform, she soon captured the million-dollar attention of Snoop Dogg (yes, the Snoop Dogg!), who bought several of her works and whom she described as being “the sweetest”. Another major sale was achieved by Katun, a previously under-the-radar artist, who sold his entire collection of works for 127.60ETH (RM1.6M) in September.

Even though the above sales generated the most media attention thanks in part to their eye-watering figures—working in a gallery, I get people asking me whether we “show NFTs” all the time, despite the oxymoron—they were mostly either ignored or derided by the traditional art scene. But the art scene isn’t composed of (just) haters; there were other exhibitions that were more critically received. Notably, Sabahan artist Yee I-Lann had her first-ever solo exhibition in her home state, which was also her first solo in Malaysia in over a decade. Borneo Heart, an extensive survey of the artist’s recent practice, featured an array of woven tikar works made in collaboration with weavers from Keningau and Pulau Omadal alongside videos and digital prints. It opened at the Sabah International Convention Centre in May this year.

Both sides of Tepo Aniya Nombor Na (Mat with a number) by Yee I-Lann, with weaving by Kak Sanah, Kak Kinnuhong, Kak Budi, Kak Roziah, Adik Darwisa, Adik Enidah, Adik Dela, Adik Asima, Adik Dayang, Adik Tasya, Adik Alisya, Adik Erna; 2020. Photo: Borneo Heart/Yee I-Lann

Tikar Reben by Yee I-Lann, with weaving by Kak Roziah, Kak Sanah, Kak Kinnuhong, Kak Koddil; 2020. The woven “ribbon” features Bajau Sama DiLaut Pandanus weaving patterns and spans over 60 metres. Photo: Borneo Heart/Andy Chia Chee Siong

If 2020 was the year of the virtual exhibition, 2021 was the year of the remote exhibition—decentralised, localised, and outside the reach of the traditional gallery. Now, it was time for us urbanites to feel FOMO as more exhibitions took place outside of the urban centres. Possibly, two years of Zoom fatigue have led artists to the conclusion that setting up a physical exhibition away from the Covid-infected metropolises for only the local residents of a place to view is still better than having an “online exhibition” (still unclear what that means) or not having an exhibition at all. FOMO has been better for publicity than virtual availability: it’s unlikely that anyone will check out your online exhibition, but they’ll check out your Instagram posts about your physical exhibition when you show it happening without them.

For the 2021 edition of their bi-annual Bakat Muda Sezaman (BMS) programme, the National Art Gallery of Malaysia will not be having their usual showcase of shortlisted contestants at their Kuala Lumpur premises (which remain closed after over a year). Instead, they have asked young contestants from all around the country to find their own spaces and organise their own remote showcases. The results of this strange exercise, which paid lip service to fashionable topics of institutional decentralisation and community power, remain to be seen. Is it a genuine attempt to decentralise the art scene away from the urban centres, or is it just a cop-out?

Other attempts at decentralisation and localisation can be found in government-sponsored arts-funding agency CENDANA’s Art In The City Public Commission grant, a new grant released this year for artists to create public installations in their local vicinities. When the agency launched their annual Art In The City programme in November, they unveiled several new public works around Malaysia, including STAR / KL by Jun Ong at The Godown, an outgrowth of the memorable star he built in an abandoned building in Butterworth in 2015. Ilham Gallery’s open-call Ilham Art Show programme could also be considered an institutional attempt at broadening horizons and promoting inclusivity.

For Port Dickson-based artist Sharon Chin, her recent exhibition Saya Suka Tempat Ini (I Like This Place) in a bungalow on the Port Dickson seafront was an illuminating example of art that’s grounded within a real context. The exhibition, which featured prints of local fauna and tide changes, continues Chin’s existing meditations on inclusive and egalitarian art-making practices. Labour & Weight, a site-specific travelling exhibition and research project between four artists (Lee Mok Yee, Okui Lala, Yeo Lyle, and Cheng Gaik Koe) also explored place and contexts. Funded under the aforementioned Arts In The City Public Commission grant, the exhibition grew and adjusted to new surroundings as it made port calls at Batu Pahat and Pulau Pangkor.

In 2021, Mark Zuckerberg changed the name of his company from Facebook to “Meta”, a reference to what techies are calling the “metaverse”, a.k.a. the digital realm as opposed to the material one. Given the diverse ways that social media has been of use during the lockdown, people now feel more assured that their events will get visibility even if their audiences can’t experience the art in person. Two worlds exist: this one, and the metaverse. Even if you miss an event in person, you can still have experiences and memories of it through virtual neural links.

Since the nation moved into Phase 4 of the National Recovery Programme in September, everything began to move with mounting momentum. As more and more sectors opened up, organisations and groups rushed to finish their yearly budget in a flurry of art-related mega-events. In Kuala Lumpur in particular, a bevy of fairs, festivals, and weekenders followed each other in rapid succession in the race to year’s end. There’s too many to list, but let’s try.

In quarter 4 alone, we had, in no particular order:

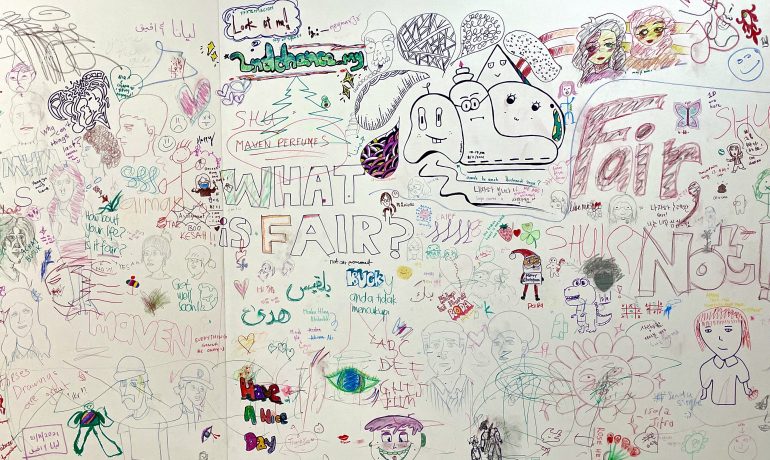

- ArtIsFair 1.0 and 2.0 at Fahrenheit88,

- Malaysian Art Ecosystem Festival at the World Trade Centre KL,

- George Town Festival and George Town Literary Festival,

- Art In The City/KLWKND,

- Bakat Muda Sezaman off-site showcases around the country,

- Konnichiwa Zhongshan and Artist of SEA’s 1000 Tiny Artworks at The Zhongshan Building,

- KL Art Book Fair at The Godown,

- CIMB Hotel Art Fair at Elements Hotel,

- Momo’s Art Fair at Momo’s Hotel…

… Have I missed anything?

Physical art returned with a vengeance in the final quarter of the year, but that doesn’t mean that galleries are enjoying the same relevance. The trend for art events is veering towards partnerships and collaborations, as curator Sharmin Parameswaran predicted in her 2019 review for Penang Art District. Art hubs, event spaces, and festivals are on the rise, not solo exhibitions in sterile galleries. (And yet, despite all their gestures towards “inclusivity” and “accessibility”, people still have a fondness for careful, big-budgeted planning and for selectivity, as the 360 artists who applied for the Ilham Art Show would probably attest to.) People seem to prefer spaces and events where they can just bump into anyone, like a lobby in a video game. Big fashionable events that bring everyone together, where you don’t know who you’re going to meet, but you know it’ll be someone exciting. The definition of curation is also looser, seeming more like a practice in building networks and managing people. Artists, curators, and organisers keep talking about challenging the elitism of the “white cube,” but it feels like the prestige of the white cube has been in decline for a while now.

Tan Lay Heong’s Between 01 installation depicting the loneliness of lockdown at this year’s George Town Festival. Photo: George Town Festival

In the pre-digital era, megalomaniacs who wanted to live forever became artists. Now, social media and the “metaverse” provide us with an easier way of extending one’s lifespan, or of having multiple identities within a single lifetime, like Virginia Woolf’s Orlando. In a time of shifting personae, where events happen in such quick succession without any time to process them, where artists and art workers find their roles constantly changing from project to project but where everyone, by default, has to be a social media manager, what is a curator, artist, or gallerist? And after all, what is art? Where is the art market?

The questions, provoked by the first lockdown, of what art’s purpose is and whether it is essential to our society still linger. As we close off a year that saw an even greater embracing of intangible worlds and ephemera, we find that the definitions and contours of things have gotten blurrier, that the stability we sought out still eludes us. Things fall apart, the centre cannot hold. It’s up to you to decide whether this is for the better or worse.

—————

Also of note

- Penang-born Peranakan artist Sylvia Lee Goh passed away in May. She was 80.

- Nasir Nadzir, a Penang-born artist who passed away last year from Covid-19 complications at the age of 31, had his posthumous retrospective at The Art Space, George Town, in May.

- After extending their previous show multiple times over a year, ILHAM Gallery finally opened a new show for a starving art public: Kok Yew Puah: Portrait of a Malaysian Artist, a survey of the life and work of the Klang-born artist (1947–1999).

- RogueArt released all four volumes of their Narratives in Malaysian Art as free PDFs. They can be downloaded here.

- After a year of mostly digital offerings, George Town Literary Festival and George Town Festival both made physical comebacks in 2021. Visual and performing artist Tan Lay Heong’s Between 01 installation utilising lockdown-imposed takeaway packaging at George Town Festival received much positive publicity, both IRL and in “the metaverse”.

- SENSORii, an immersive, large-scale art experience at REXKL curated by Yap Sau Bin and organised as part of CENDANA’s Art In The City 2021 programme, booked out all of their slots, achieving over 10,000 visitors. The exhibition featured multimedia works by seven artists.

Ellen Lee is a writer based in Kuala Lumpur. She is interested in all forms of culture, from fine art and poetry to trap music and anime.