Reflecting on her involvement in projects that mix art and social change, the writer ponders what happens when we try to measure the success of these efforts, and suggests one field in need of change.

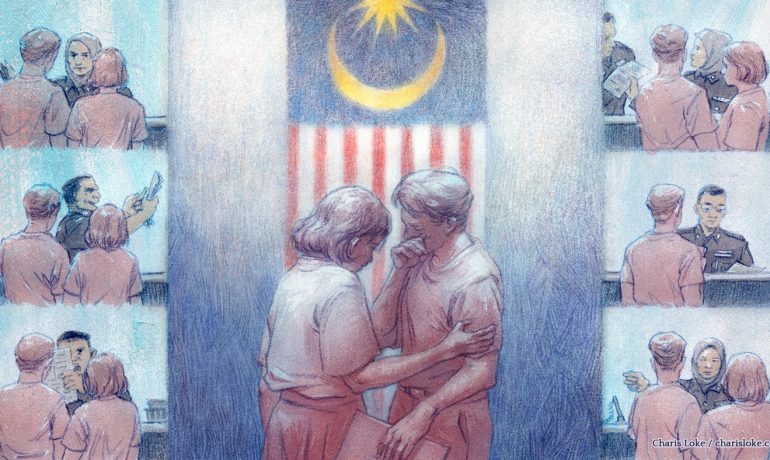

By Charis Loke

As an illustrator, I’ve drawn posters, editorial illustrations, explainer comics and visual documentation for civil society organisations and publications. I’ve also commissioned and edited many of the same. I hope that work has been worthwhile—but does it count as ‘art for social change’? And what does that entail?

As a general definition, we might say: art practices that are used to effect a change in society, to transform behaviours and norms. These practices are described by various terms such as community-engaged arts, community arts, arts for good, participatory art-making, and so on. We might also note a distinction between artists who merely seek to depict social issues and structures, and artists who attempt to directly engage with or intervene in those structures. More importantly, though, how do we measure the impact of these kinds of projects? Here, I consider some of the questions that arise for artists involved in art for social change, particularly those collaborating with partner organisations. I’ll reflect on my experiences in three roles: illustrating and art directing visual stories; designing and facilitating cultural education workshops; and curating a community storytelling experiment.

Sketches from Bersih rally in 2015. Sharpie on paper.

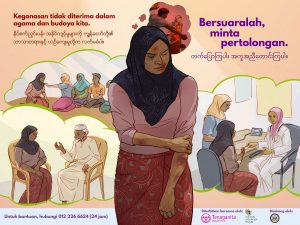

Campaign poster for Tenaganita. Digital illustration.

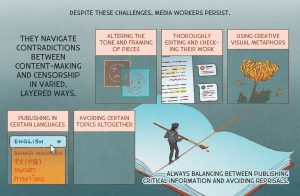

Crop from Media Work as Resistance comic. Digital illustration. Art and writing by Charis Loke, research by Fadhilah Fitri Primandari, Samira Hassan, Sahnaz Melasandy, editing by Jacob Goldberg.

I wouldn’t claim that the visual stories I’ve worked on spark social change by themselves, although it’s important we ensure there’s room and resources to create them—this kind of work is transformative for the creators. A comic might be part of an advocacy campaign but the research, outreach, training, lobbying, protesting, and policymaking work—done over years and years—are what’s more likely to mobilise people and create positive change. At best, I could say that these comics and posters helped to create short-term awareness or prompt some readers to ask questions about an issue. At worst, art becomes the creative equivalent of whitewashing, used by institutions and organisations to smooth over unsightly problems and disparities. Designwashing, if you will.

Youth Arts Camp participants at Chowrasta Market. Images by Arts-ED.

More rewarding have been the community-based projects I’ve been involved in. These projects aim to engender positive social change by creating space for people to express themselves, build their capacity, and strengthen communal relationships. With Arts-ED Penang, I’ve designed and facilitated workshops for their Youth Art Camps (YAC), which use Chowrasta Market as a site. These are part of a larger creative art education project developed to fill a need for place-based programmes that highlight local knowledge. Students from public secondary schools used art forms to make sense of and share their learnings from the wet market: observational sketching to analyse ergonomics, illustration to visualise waste management practices. They engaged with the market community and developed skills such as interpersonal communication, empathy, and critical thinking. The process used in YAC helps shift their perceptions of the market and the people who use it.

Other projects use narrative work to document experiences and spark social change. I’ve been working on Innovation for Change – East Asia’s Libraries of Resistance, which collects stories of struggle, hope, and inclusion for civil society to learn from. This is an example of a community-based project where storytellers (artists and activists) use their art practices to elicit and retell these narratives, as well as facilitate artmaking with specific groups: a mix of artist-driven and artist-facilitated participatory processes. Participating storytellers consider ethics of care and responsibility towards their communities, both as ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders’. What does being transparent about the project with community members entail? How might they equitably allocate funds to collaborators? How do they gather stories without being extractive? How do they negotiate consent as an ongoing relationship? The connections formed between communities and storytellers and the organising team are important outcomes too, not just the stories. Publishing later this year, the nine stories highlight a range of issues—like indigenous resistance against dams; intergenerational conflict amidst political turmoil; living with joy and disability—and are told through portrait songs (biographical songs), dance, comics, collaborative zines, poetry, multimodal webpages, and videos.

One recurring question we’ve asked during the project is: what might a ‘successful’ story or public engagement event look like? And more generally: how do you know a work of art has made social change? Who gets to measure this, and by what metrics and methods? Social scientists speak of the double social life of methods: methods shape and are shaped by the social world they describe. Do our measuring tools create realities where, say, impact that is visible is prioritised over other kinds of impact? A world where “that which cannot be measured loses its value in all but name”, as Sharon Chin puts it?

Imagine a post-project evaluation form that only asks for audience numbers and self-reported behaviour change (measured by a run-of-the-mill Likert scale survey). This form is built on specific ideas about success. It ascribes a certain value to those metrics. It’s also part of a wider assumption that our measuring tools work, that the change we want is measurable, that measuring inherently helps us be more effective in creating social change. Additionally, social change tends to happen over time frames that are much longer than those of typical non-profit programmes or grant-funded projects. What happens when a funder or members of a community clamour to see quick “results”? How do we make room for the very likely possibility that an art project fails to bring about its intended outcome—and has unforeseen, negative outcomes instead?

Crop from NN Explains: Authoritarianism comic. Digital illustration.

Finally, let’s consider: what about a work of art that aims for social change but was created through exploitation? This includes appropriated knowledge from marginalised groups, uncredited sources, unpaid labour, and ill-treated collaborators or team members. Working in the arts or nonprofit circles, one hears whispered warnings: a festival paying certain artists months late; an activist verbally abusing their colleagues; an art grant with ‘backdoor’ recipients; an auteur with impossible expectations and an unpredictable temper.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. Using Howard Becker’s conception of art worlds, if art is the result of collective action and co-operation in a network of people, then one place to enact social change is in the very production of art. What beliefs, norms and infrastructures in the making, funding, and sharing of art are due for change? I could list a few:

- It’s okay to underpay artists for work that’s for a good cause.

- The artist or funder owns copyright of the work; ownership and credit isn’t shared with the community members who contributed knowledge and effort in a project.

- Grant funds cannot be used to cover living expenses like childcare and healthcare for artists.

- Projects are framed within rigid, funding-driven timelines.

As we make art about + for + with our communities, we can choose to make the change we seek—for instance, implementing flexible funding that accounts for artists who are parents or who have mental health needs—and over time, shift the needle on these norms and structures. That would be a welcome change.

Thanks to Adriana Nordin Manan, Deborah Augustin, DW, Joelyn Alexandra, Minxi Chua, Max Loh, Rupa Subramaniam, and others for recent and old conversations that shaped this article.

Charis is an illustrator, editor, and lover of nutmeg punch. Formerly New Naratif Comics Editor and Illustrations Editor, she’s worked with artists from Southeast Asia and the diasporas to tell visual stories that explain the world around us. At Arts-ED Penang, she designed heritage education projects for youth, including ergonomics and waste management explorations at a wet market. Charis now curates community storytelling projects and recently completed an MA in Visual Sociology with an interest in drawing and mapping as research methods.

Header image: Editorial illustration for ‘Amid Tourism Push, Malaysia Keeps Binational Families Apart’ by Liani MK. Pencil and digital illustration.

Unless otherwise stated, all illustrations are by Charis Loke.