If a festival is a performance itself, what stories are Penang’s 3 long-running art festivals telling? Former festival directors re-visit the festivals they directed and unpack their stories.

By Lee Kwai Han

Every first weekend of December since 2004, visitors from different parts of the world flocked to Penang to be part of the Penang Island Jazz Festival (PIJF). PIJF was the longest-running art festival in Penang until it stopped in 2018. Meanwhile George Town also hosts various art happenings, big and small, all year round. Another two major festivals are the George Town Festival (GTF) and George Town Literary Festival (GTLF), since 2010 and 2011 respectively.

In June, Penang’s Chief Minister, Chow Kon Yeow launched the Strategy for Economic Ecosystem Development 2023–2028 (Penang SEED). “Festivals” is listed as one of the creative industries in the document. But what do festivals mean to Penang?

Former festival directors, Paul Augustin, Joe Sidek, and Bernice Chauly look back at the time when they each helmed one of the three major art festivals in Penang and share their visions and challenges faced.

Putting Penang on the global map

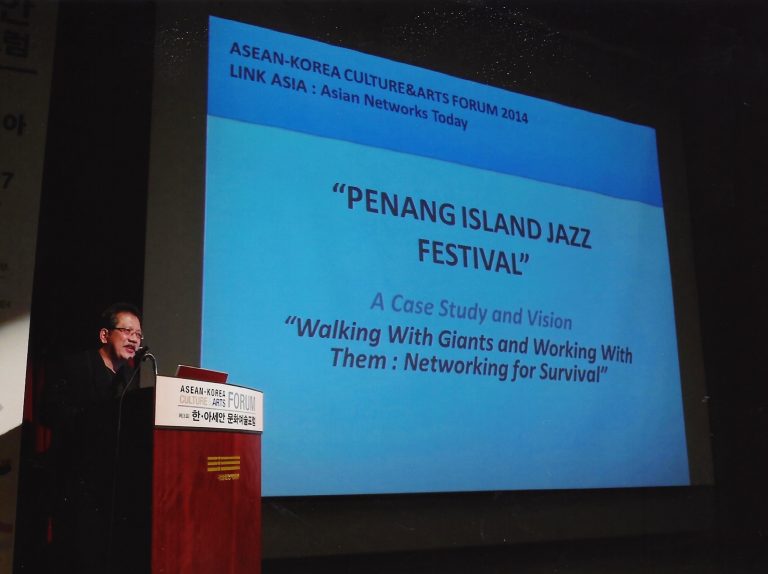

In 2004, Paul Augustin started Penang Island Jazz Festival as a long-term business venture for his event management company. He put his extensive experience and connections in event management and as a musician as well as knowledge of the industry into realising his idea.

He had not been aiming to go big-scale like the Java Jazz Festival. Instead, “it’s a matter of how you place your festival to be important,” he says.

“Towards our tenth year, eleventh year, a lot of Norwegian artists want to play in Penang, because once they play in Penang, they have the possibility or opportunity to play in the London Jazz Festival.”

His idea worked: PIJF became an important node in the local and global jazz industry.

Meanwhile the new Penang state government under Pakatan Rakyat set out to put Penang on the global map. First, they got Joe Sidek on the job.

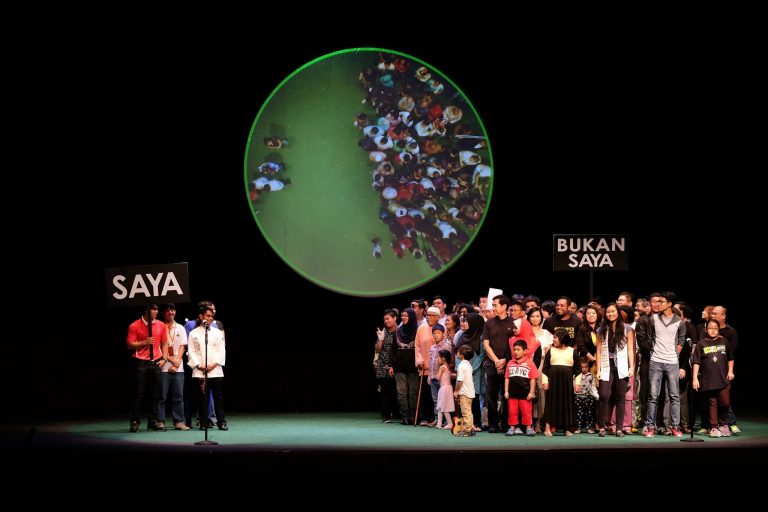

“My duty was to build a festival for the world. So that the world looks at Penang as the centre, a go-to place,” says Joe in reminiscence. He directed the George Town Festival (GTF) from 2010 to 2018. The month-long GTF showcased international and local performances and exhibitions.

The core of a festival

For Joe, “every festival should have its own narratives, or psyche, because the festival is about your city.”

He recalled a show in 2011 about the story of the 7th wife of Cheong Fatt Tze, a wealthy Chinese industrialist in the late 1900s. Joe says, “You cannot do a show like that anywhere else in the world.” It ran for three nights in the Cheong Fatt Tze Mansion in George Town, which Cheong built and lived in. “It’s exclusively Penang. Only in Penang. It’s important for us to build that Penang brand that sells the uniqueness of the city.”

Also in 2011, the Penang Global Tourism engaged Bernice Chauly to curate a literary festival under the state government.

Chauly started the George Town Literary Festival with the theme of “History & Heritage: Where Are Our Stories?” It featured 5 writers: Tan Twan Eng, Shih-Li Kow, Farish Ahmad Noor, Muhammad Haji Salleh, and Iskandar Al-Bakri

“I chose the themes based in an organic manner, first starting with historical concepts and delving into colonialism and migration, in trying to present Penang to Malaysians and a global literary community.”

Over eight years, GTLF grew from featuring five Malaysian writers to over 100 participants from 25 countries, including the Netherlands, Belgium, Iceland, Canada, Scotland, Sweden, Australia, Germany, the UK, Ireland, and India.

“The networking aspect of the festival was crucial, as Malaysia was not seen as progressive when it came to the arts. A lot of convincing had to be done, sometimes to even convince writers that they would be able to speak freely, and not face persecution.”

Holding the line for creative practice

However, “in 2016, the festival’s ideals and Malaysia’s culture of control clashed,” as Kate Mayberry encapsulated in her essay “Literary Town” (The Best of Mekong Review, Page 366).

Political cartoonist Zunar was arrested under the Penal Code and Sedition Act after his exhibition with GTLF got disrupted. GTLF’s stand on free speech was put to test.

Following the arrest, Bernice Chauly condemned the arrest of Zunar and re-iterated GTLF’s commitment to free-speech.

“GTLF was the last bastion of free-speech in Malaysia, and in Penang, we could say the unsayable and debate it. This was a truth I held close to, and I stood by this creative vision,” says Chauly.

When GTLF won the London Book Fair’s Literary Festival Award in 2018, the judges ruled that, “In a strong field, George Town Literary Festival stands out as a vibrant, diverse and brave festival that engages with a wide community of voices, speaking to the world from a complex region”.

Global or local?

On engaging the local and global art communities, Joe Sidek had been criticised for not supporting local art practitioners enough in his nine years directing GTF.

“I wanted our own practitioners to come and see, and benchmark themselves with global standards. You’d want to be global,” says Joe. While GTF was positioned as an international festival, Joe hopes the shows he staged in GTF had inspired people in Penang.

He thinks that the current GTF has been performing well as a popular festival. “But does it help nurture culture?” he asks.

On the other hand, Augustin had enjoyed the freedom of running PIJF independently. He thinks a festival is a place of discovery. “When they (local musicians) play, they make contact with other musicians, international foreign musicians, other festival directors, and journalists.

“If you come with an open mind, you know how much you can gain.”

Looking back at his nine years with GTF, Joe thinks the missing puzzle piece is another festival that grooms and nurtures local art practitioners towards performing on global platforms.

“But technically, the state needs to know what it is that [they] want [from a particular festival],” says Joe.

Art Festivals as Creative Industry

Now, for the state government to know what it wants to achieve through a festival is to ask how the state values art festivals. It’ll ultimately show up in the state’s policy and resource allocation for the festivals.

For Joe Sidek, GTF’s media and PR value speaks volumes for its return on investment (ROI) for the state. Meanwhile, Augustin thinks the economic valuation of an art festival goes beyond that.

“Ticket price [of PIJF] might be 80 ringgit, but the amount of money [spent in Penang] when a person comes [for the festival], it comes close to a thousand ringgit. Two to three nights accommodation. Transportation. Makan (Food),” Augustin explains how a festival contributes towards Penang’s tourism receipts.

Nonetheless, in 2018, Augustin announced the halt of PIJF, funding being the major obstacle he faced.

“Negotiating, looking at contracts, applying for permits, looking for sponsors, all these things are work. Eight to ten months [of work], for three days or four days [festival],” says Augustin.

He decided to focus his resources on running Penang House of Music which he co-founded in 2016.

On the other hand, despite being state-funded, Chauly shared a similar plight of resource constraint in GTLF. “I got no further support as we simply did not have the budget to hire another curator to assist me.”

Once, she had envisioned GTLF to become self-sustaining and independent from the state government. She wanted GTLF to have its own board and full-time employees and be supported by an arts council. But the idea had not been accepted by the state.

In 2018, Chauly decided to leave GTLF after eight years of constant fighting for adequate remuneration and project budget, permanent position, and a self-sustaining GTLF, but to little yield.

“Art and culture is a commodity. Art and culture is a basic need. Art and culture is capital,” Chauly says. “Artists and practitioners who make art and culture cannot exist in an economic vacuum, and need to be at the very least, able to sustain their livelihoods and their craft.”

Microcosm of the Art Ecosystem

The newly-launched Penang SEED has not spelled out specific strategy and possible action pertaining art festivals. But learning from Penang’s very own long-running art festivals would give us clues for visionary and strategic planning.

“Festivals are not just for entertainment. There is a rationale behind why we create festivals. What message is important? We can share messages,” says Joe.

Art festivals may be shaped in the hands of festival directors. But the government, art practitioners, and festival-goers’ understanding and imagination (or its lack) about art and society eventually entwine into the core of each festival, and Penang’s art and culture ecosystem.

——————————————————————————-

Further reading:

- Alexander Fernandez, Lim Sok Swan and Pan Yi Chieh. The Future of Creative Industries in Penang. 22 February 2019. https://penanginstitute.org/publications/issues/the-future-of-creative-industries-in-penang/

- Shirvani Dastgerdi, A., De Luca, G. Strengthening the city’s reputation in the age of cities: an insight in the city branding theory. City Territ Archit 6, 2 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40410-019-0101-4

- Arts-ED. Penang Arts Ecosystem Map 2021. April 2022. https://www.arts-ed.my/online-materials/2021/penang-arts-ecosystem-map-2021

Cover photo shows the crowd at the main stage of Penang Island Jazz Festival in 2009. Photo courtesy of Paul Augustin. Photographer: Michael Lee

Lee Kwai Han manages arts and environmental education projects in Penang. Despite her training in engineering, she believes arts is the software solution our society needs.