Can dance or movement be seen as a form of therapy, and what kind of healing does it bring? We speak to Hilyati Ramli and Aida Redza who use dance and movement to bring a sense of unity between body, mind, and spirit.

By Miriam Devaprasana

Over the last 30 years, there has been increased attention to arts intervention in healthcare. Broadly speaking, art in healthcare is a multidisciplinary approach that uses the arts as tools for improving health and healthcare experiences. Many creative and artistic processes, including music, drama, visual arts, and dance or movement, are implemented as therapeutic models to promote growth and change.

The field of dance/movement therapy (DMT) in Western medicine was spearheaded by Marian Chace in the early 1940s. Its gradual acceptance saw the founding of the American Dance Therapy Association (ADTA) in 1966, which supported DMT as a profession. The ADTA defines DMT as the “use of movement as a process which furthers physical and emotional integration of an individual” (Sandel, 1975). The foundational perspective to using dance/movement as therapy is understanding the interdependence between movement and emotion.

This means there is a relationship between the mind and the body, where the state of our minds or our mental capacities profoundly affect our attitude and feelings (emotions). This, in turn, affects the state of our bodies, both positively and negatively. Therefore, dance or movement is a way of (re)connecting the body and the mind, using the forms therapeutically to bring a holistic integration of our emotional, physical, cognitive, and spiritual selves.

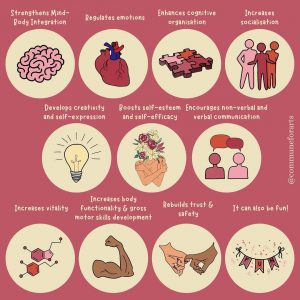

Reasons for DMT by @communeforarts

Dance and Movement as Therapy in Malaysia

In Malaysia, the conversation surrounding art intervention in healthcare has also led to the development of its implementation, with multiple strands of benefits being seen in the local context. Not only is it regarded as having a huge positive impact on the quality of life in adults, but it is also seen as an alternative approach for communities who show resistance or concerns towards treatments with (assumed) negative side effects on the body.

While the literature on arts intervention in Malaysia is growing, research in DMT is still in its infancy. However, existing forms of its use have shown a positive impact. A recent study includes one which examined a breast cancer survivor group called the Candy Girls, which incorporated weekly dance sessions for self-rehabilitation. Survivors engaged in various forms and dance genres like Zumba, yoga, and Malay folk dances like the Joget and Zapin. The study showed the therapeutic value of dance as a form of rehabilitation for physical and mental well-being. It also positioned DMT as a tool in building solidarity and powerful communities for breast cancer survivors. You can read more about the study here.

Slightly closer to home, a team of researchers at Universiti Sains Malaysia have been working on a sound-dance approach to raise advocacy on mental health and well-being within educational settings. We spoke to Hilyati Ramli from The Healing Art Project (THAP) to provide insight into the techniques she uses within the programme.

The Healing Art Project at Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM)

In 2018, Dr Kamal Sabran and Hilyati Ramli from the School of Arts at USM kickstarted a multisensory art programme combining elements from traditional music composition and instruments, sound design, and guided body movements as tools for art intervention to promote awareness and advocacy for mental health and well-being. You can read more about THAP here, and here.

Hilyati Ramli, a lecturer, researcher, and theatre practitioner, is also the choreographer who developed the body movement aspect of THAP’s sound-dance module. She shared that the guided body movement allows participants to express their feelings and emotions to reduce stress and anxiety. Hilyati’s approach to body movement is based on a sequence of stretching techniques, adopted and adapted to suit the wide range of participants they welcome, including those with little to no background in dance.

Kelas Tidur, as part of the ongoing The Healing Art Project. Photo courtesy of @kamalsabran, taken from The Healing Art Project.

Each session begins with a live music performance, which invites participants to engage with their minds and adapt to the space to be present in its current environs. Following a period of initial preparation, participants are then guided by Hilyati, with instructions for participants to engage with their body through the stretching movements. She finds that these basic techniques are not only appropriate but enough to stimulate a sense of calm and relaxation. This is primarily owed to the benefits of stretching and its effects on blood flow, increased circulation, and how it aids in stabilising our moods. After a series of stretching techniques, participants are invited to lie down and sleep for 30 minutes. This enables participants to remain in that space of rest, with the goal of preserving calm and relaxation. At the end of each session, participants are encouraged to share their experiences, feelings, and whether the programme affected their stress levels.

While the team are currently working on data analysis for publication purposes, Hilyati shared that their research has shown positive impacts on reducing stress and anxiety among the participants. As someone who practices guided meditation, I can attest that using basic stretching techniques is helpful for participants to incorporate into their lifestyles in the long run, especially if they cannot always make it to programmes or sessions like THAP.

The value of culturally tailored art forms.

Another arts practitioner who facilitates dance/movement sessions in Penang is Aida Redza. A luminary in the Malaysian dance scene, Aida has been creating and holding space for people across ages to reconcile the physical and spiritual aspects of being. Like THAP, Aida weaves in elements of local art forms (specifically through dance and movement), bridging familiarity and encouraging an openness to the value of traditional and cultural forms of dance and movement.

A primary reason behind Aida’s approach is in light of how the discourse surrounding dance, health, and therapy is primarily framed within the Western lens. Additionally, very few considerations are being made on how traditional dance forms have been used for thousands of years, as it is related to healing, fertility, birth, sickness, and death (Molinaro, Kleinfield and Lebed, 1986). This is partly due to the general perception that dance forms like Mak Yong and Mayang Teri are associated with ceremonial or shamanistic rituals, rendering them increasingly hidden and neglected art forms. Yet most traditional and cultural dance forms across East Asia and South Asia share a similar underlying principle—that the body and mind are united. This is a core belief on which DMT is grounded.

Aida in an on-site experimental performance titled ‘ANGIN OMBULAN’ for George Town Festival 2022. The performance revisited the traditions of healing in choreography, and uses traditional music for a therapeutic multisensory experience towards healing and recovery. Photo courtesy of George Town Festival 2022.

Therefore, Aida incorporates culturally tailored movement, encouraging participants to engage with the notion of ‘buang angin’ (Western language would equate the concept to ‘energy’, ‘vibes’, or ‘frequencies’). In this regard, Aida brings in elements of local dance or movement to aid participants in identifying internalised energy that needs to be released for the body and mind to find unity. Aida finds that the approach helps in the flow release, which then triggers the body to react or respond to the energy shifts happening internally. In simple terms, reactions like laughing, crying, exclamations, or shaking are simply the body’s external response to the internal shifts in energy. These reactions are encouraged as they become pathways for release to take place, gradually removing the things that restrict healing and unity of the body and mind.

Conclusion

A sceptic might scoff at the idea of dance as therapy, but perhaps the approach should not be to question whether it works or not. Rather, we should view dance and movement as tools to cultivate an increased understanding of our bodies and how they hold our emotions and mental capacities, deliberately carving out time and space to explore how we feel, why we feel, and what it means to our journey of becoming.

When asked what the general feeling after each session is like, both Hilyati and Aida remarked on how there seems to be a shared experience of calm and rest, a unified sense of lightness, and increased knowledge and understanding of the body, mind and soul. Dance or movement, therefore, becomes the body’s way to speak a language without words, through which our internal and external selves communicate power, grief, survival and freedom. Slowly, healing in any and all forms is uncovered and shared, with dance becoming a catalyst for personal and collective healing.

Additional links:

Click here to watch a presentation by Dr. Kamal Sabran and Hilyati Ramli on their research through THAP. THAP is also an ongoing project. Follow their Instagram for more information on upcoming programmes.

For those interested in attending Aida’s classes, here’s a snippet of what to expect. Follow her on Facebook for more information.

Cover photo by Patrick Hendry on Unsplash.

Miriam Devaprasana is an observer and dabbler of creative expressions. She is the founding member of Dabble Dabble Jer Collective, a Penang-based arts collective, and is currently pursuing a PhD in Urban Sociolinguistics. Miriam hopes that one day, her work will help form a new way of thinking ‘Malaysia’. Read her blog at mdev16.wordpress.com