Is Artificial Intelligence a tool that that authors should embrace? Various authors and publishers discuss their approaches to AI and what they foresee for the future of the publishing industry.

By Art3rius

Fadzlishah Johanabas is excited about artificial intelligence (AI). The neurosurgeon and author of the science fiction short story collection, Faith and the Machine, believes that generative AI is paving the way to incredible possibilities.

Fadzlishah has been using AI to help him generate plot outlines, envision characters, and build worlds beyond his immediate experience in the medical field. His most recent work done with human and AI collaboration is a story set in the days of imperial Malacca.

“I am a highly visual person. With Midjourney, especially with the more photorealistic version 5, I bring the characters closer to how I imagine them to be. I tell Midjourney their ethnicity, age, facial features, clothes and background settings.”

He also uses ChatGPT to discuss story lines, plot holes and character development as if the chatbot were a sounding board or writing partner.

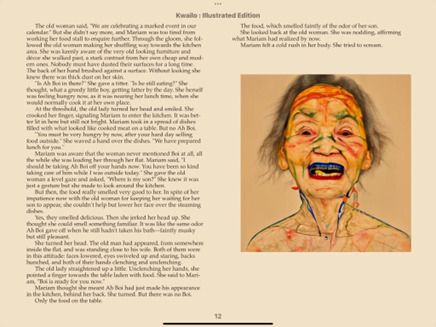

Images of Malay pahlawan that Fadzlishah generated using Midjourney to illustrate and conceptualise his work.

He is not alone in making use of AI to enhance his writing process. Leon Wing, whose self-published works include a novel called Little Book of Tuala and a collection of strange short stories called Kwailo, has made use of AI to generate illustrations for his works.

He is particular about the aesthetic choices that he wants. “I use AI models that generate the kind of art I’m looking for: nothing as aesthetic as the ones depicted beautifully and intricately ‘drawn’, nor ones that blatantly shout out AI. They must look naive and rough, as if drawn by the human hands of an ordinary artist, rather than an expert.”

Artificial Intelligence, Real Problems

But not everyone is as excited about AI in the creative sphere. Concerns about generative AIs and their impact on the creative industry have ranged from the ethics of data scraping to fears of machines gaining sentience. Recently, Bloomberg predicted that AI disruption may affect as many as 26 million jobs out of their surveyed companies alone.

Creatives in Malaysia are also paying attention. Alan Wong, an editor, has expressed concern that the rise of AI-generated material will enable writers of business and self-help books to claim others’ ideas as their own, affecting their credibility.

“Can they say they own [the ideas generated by AI], or claim they are experts in whatever they are ‘writing’ about? Can they be trusted to provide insight and guidance on the topics in their works?”

The idea that by using AI one is ‘stealing’ ideas and claiming them as one’s own is also one that troubles others in the creative sphere. A writer and legal professional who wishes to be quoted anonymously states that copyrighted works were fed to the machine without the consent of their creators, an act she considers unethical.

“Copyright law is a bit archaic in the sense that it has never contemplated how the human brain can now function together cooperatively with an artificial brain. The whole philosophy of copyright in this regard needs to be revisited in order for us to continuously help artists and authors protect their original idea.”

As of now, although American courts have ruled out copyright claims by AI-generated material, Malaysia has not yet made any ruling regarding copyright of AI-generated work, whether they are created fully or partially by the AI.

“The closest case is the case of Wedding Galore Sdn Bhd v Rasidah Ahmad (2016) 6 CLJ 621, when the court determined that a photographer who used Adobe Photoshop as a tool to improve her photograph was entitled to the copyright to those photographs. [Hypothetically] if AI-related cases were to be brought to dispute, this same principle can show that the original author was entitled to the copyrights of his work because the AI merely acted as a tool to the final work,” she further adds.

Making Opportunities Out of Threats

The legal issues have not stopped creatives from worrying—or adapting. While some publishers abroad have declined to publish works generated or assisted by AI, a number of Malaysian publishers are already adjusting to a world where AI-generated works may be the norm.

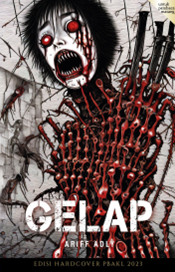

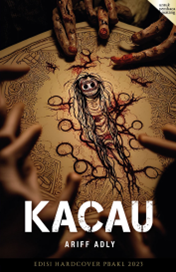

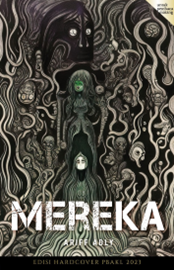

Publisher and film producer Amir Muhammad has published reissues of Fixi’s bestselling novels in special edition hardcopy and used AI-generated art as their covers. Designed by Lesly Leon Lee by Stable Diffusion under his Deep.latent.space project, they connect the mysterious way AI builds connections from data corpuses with the sense of horror and unease they inspire.

Three special editions of re-issued Fixi novels with AI-generated covers. Each was made by Lesly Leon Lee as part of his Deep.latent.space collection.

Amir has also not excluded the possibility of publishing works that are AI-generated.

“We are in the business of selling stories. It doesn’t really matter how the stories are generated as long as we don’t get into legal trouble. The kind of stories that do well are the ones that get positive word of mouth—by human readers. If something by an AI manages to achieve that, we won’t stand in the way of reader enjoyment.”

Ivy Ngeow is another Malaysian who has published AI-generated material. The anthology of AI-generated works called AI Creative Writing Anthology: 20 Authors Share How to Use Computer Tools is edited by computer scientist Geoff Davis and published by her London-based publishing house, Leopard Print.

Each story comes with an interview with the author and a statement of their working process. The anthology includes stories that make use of archaic models like ELIZA.

Other publishers remain cautious. A representative from Gerakbudaya Publishing acknowledges that AI is ‘growing rapidly’, but that it is a path that they are treading with care. As of now, the social sciences publisher believes in prioritising human-written works, but that determining authenticity will be a challenge.

“Is a work considered unauthentic if an author keys-in a prompt to produce an initial draft, but then edits it later to insert his voice and view in the text? We believe these questions arise due to the lack (or absence) of regulations that control and guide how AI is used.”

In the absence of a foolproof method to determine human authorship of a text, Gerakbudaya will rely on the consistency of the voice of the author.

“Human works have their own tells, and this is what we will look out for. The typical human being will project errors, flaws, and biases in their thinking, which are specific traits for each individual. The narrative that an author wishes to tell, along with those aspects, will always reflect in their writing, be it emotionally, critically, or in the language of the text itself,” states Gerakbudaya, adding that their goal to publish works related to the social sciences that are critical, thought-provoking, and broadcasts the voice of minorities remains the same.

Maintaining Humanity in an Age of Machines

Yet debates about AI-generated art go beyond the legal sphere and are deeply connected to ways that we think about art and human creativity. What role does human creativity play in a world where they can be easily outmatched by machines?

Fadzlishah Johanabas is firmly on the side of human-machine collaboration. He believes that AI use has helped him out of a ‘writing slump’ and credits ChatGPT for motivating him by silencing his inner critic. He also believes that prior knowledge and skills are necessary to maximise the AI’s potential:

“With Midjourney, when you want to achieve cool portrait photography, you need to know the angle and distance of the shot, the type of lens, background imagery to frame the picture, and the dimensions of the image. The same goes with ChatGPT. Simply asking it to outline a novel won’t help much. You need to know the type of beat sheet to use, the kind of story you want to tell, terms like immediate scenes, exposition, and rising tension, and also how to steer the AI so that you get the story that you want to tell.”

Amir Muhammad believes that a human connection is necessary for readers although this does not necessarily need to include a physical presence:

“The bestselling Fixi book of last year was written by Abstrakim, who has never shown himself publicly, but has many followers on Telegram. An AI work may produce something more technically polished, but readers don’t look only (or mainly) for technical polish; they want to feel they are engaging with a real person.”

Although Alan Wong believes that AI-generated works will increase the volume of written material competing for attention, the process still involves human intervention, even if they serve only as a content strategist and vetter.

“Current AI models still need human input, so we’re comparing human authors who have embraced automation with those who still believe in toughing it out for the work to be authentic,” he states.

“Ultimately, readers (and publishers) win, because they have more material to look forward to. However, quality is still key, and going through all that material for favourites will be a slog, but discovering the good stuff will be even more of an adventure. So what if there’s more than what one can possibly read? Hasn’t that always been the case?”