After numerous cases of censorship, an avalanche reaction shows us a highly frustrated arts community questioning the state of creative freedom in Malaysia.

By Sonia Luhong Wan

On 10 February 2020, Malaysian multidisciplinary artist Ahmad Fuad Osman wrote an open letter on Facebook and Instagram. It condemned the National Art Gallery’s (NAG) decision to remove four of his exhibited artworks following a single complaint as ‘arbitrary, unjustified, and an abuse of institutional power’.

The post quickly became hot news for the week.

View this post on InstagramA post shared by Ahmad Fuad Osman (@osmanahmadfuad) on

Curated by Shabbir Hussain Mustafa, senior curator at the National Gallery Singapore, At The End Of The Day Even Art Is Not Important (1990-2019) is Fuad’s mid-career solo exhibition; an exploration of how narratives and histories are told through seven cycles of research spanning three decades of his artistic journey. The exhibition has been showing at NAG, also known as Balai Seni Negara, since 28 October 2019 and is slated to end by 29 February 2020.

It is worth noting that the four ‘controversial’ artworks—untitled (2002), Dreaming Of Being A Somebody Afraid Of Being A Nobody (2019), Imitating The Mountain (2004) and Mak Bapak Borek, Anak Cucu-Cicit Pun Rintik (2016–2018)—were among those approved and publicly exhibited by NAG itself to a generally positive reception for nearly four months until the alleged complaint by one of its board members.

In response to Fuad’s open letter, NAG’s media statement defended its National Visual Arts Development Board’s (NVADB) decision to protect ‘the dignity of any individual, religion, politics, race, customs, and the country’, with its Director-General, Amerruddin bin Ahmad, asserting—very reassuringly, no doubt—that ‘the exhibition is a process and not the final product’.

Indeed, NAG, also the organiser of the upcoming KUL Biennale 2020, has a notable track record of treating exhibitions as a mere process. Local and international recipients of this curatorial approach include: Vienna Parreno and Krzysztof Osinski’s Self Mark 1 and Self Mark 2 (in 2006), Cheng Yen Pheng’s Alksnaabknuaunmo and Izat Arif Saiful Bahrin’s Fa Qaf (in 2014), as well as Pusat Sekitar Seni and Population Project’s Under Construction (in 2017).

However, NAG is only one out of many. Other instances include the Japanese Foundation Kuala Lumpur’s and Bank Negara’s treatments of Pangrok Sulap’s Sabah Tanah Air-Ku (in 2017) and Azizan Paiman’s MKKEN (in 2019) respectively. In a more extreme example, well-known artist Zunar was arrested and charged under the Sedition Act in 2016 after holding an exhibition of his political caricatures in Penang.

Pangrok Sulap’s Sabah Tanah Air-Ku. Courtesy of Sonia Luhong Wan.

It is important to recognise that NAG’s high-handedness and lack of transparency over the incident are merely a product of Malaysia’s long-standing culture of censorship and top-down way of handling matters. Too often, censorship is initiated by a few without first consulting all stakeholders involved, including the artists themselves and members of the public.

That a handful of people get to independently decide how society should think, feel, and express, contradicts a culture of critical thinking, insults the intellectual capacity of Malaysian society, and subsequently stunts the development of arts in Malaysia.

Unlike previous cases of censorship, however, Fuad’s has garnered an unprecedented outpouring of support. After nearly a week of public outcry, NAG finally reinstated all four artworks on 16 February 2020.

View this post on InstagramA post shared by Balai Seni Negara (@nationalartgallerymy) on

While undoubtedly a victory and a step forward for the Malaysian art scene, this incident also reveals the disturbing reality of arts censorship in the country: that arts institutions such as NAG and other galleries are also proponents of censorship. One is tempted to ask: Who then, can artists truly rely on to safeguard their freedom of expression? Is the artist merely a content provider? Or is the artist also a primary stakeholder, whose interests and rights are equally worthy of protection?

View this post on InstagramA post shared by Pakha (@pakha_sulaiman) on

The level of moral and practical support that Fuad received—from fellow artists, art collectors and other members of the art community, government representatives, the media, and the public—is what every artist rightly deserves when confronted with censorship. However, it also signals a high need for the Malaysian arts community to earnestly gather and formulate a cohesive support and response system.

Commenting on the incident to Plural Art Mag, Joshua Lim, Director of Malaysian art gallery A+ Works of Art, reminds us to ‘keep pushing so that our cultural institutions fully appreciate what it means to be transparent and accountable, and so that open dialogue becomes the rule and not the exception’.

In his comment to the Malay Mail, poet and art activist Pyanhabib reiterated the need for art administrators who are ‘brave enough to do their work and defend their collective decisions’.

Will Fuad’s case go down as yet another viral post, or the start of active, sustained efforts by all quarters to safeguard creative freedom in the country? Hopefully, we wouldn’t have to wait until the next censored artist to know.

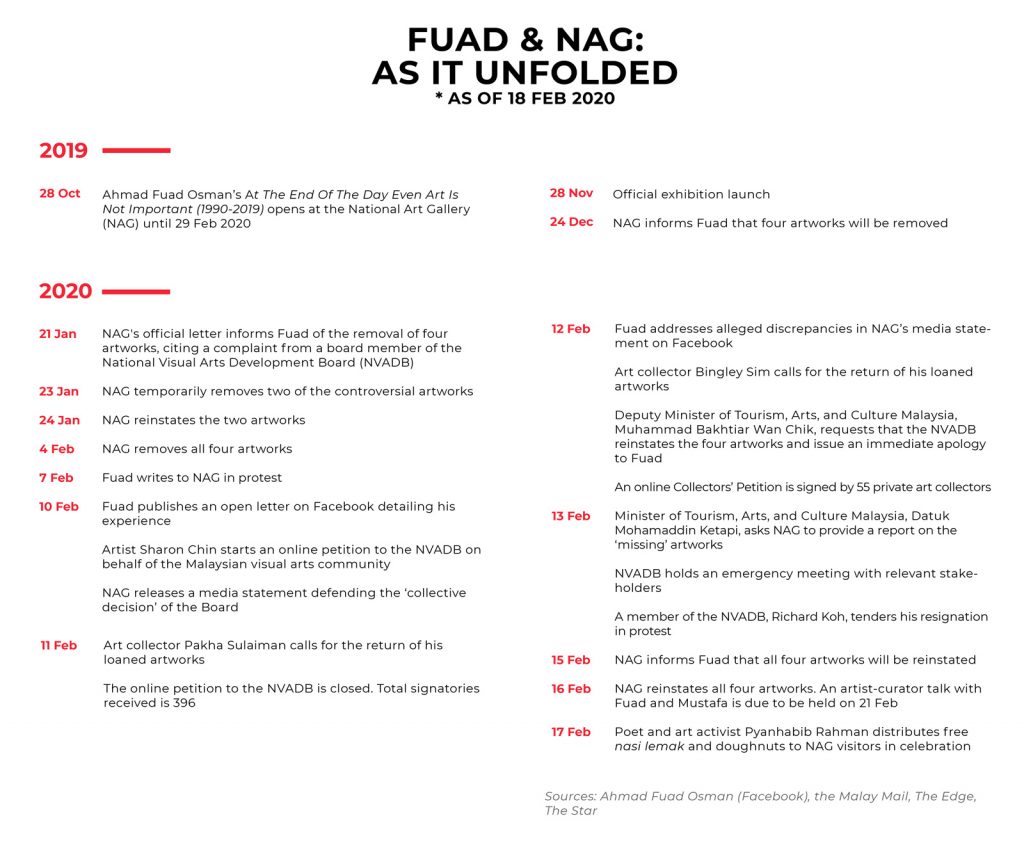

A timeline of events. Courtesy of Sonia Luhong Wan.

(Click to expand image)

Cover image source: Facebook.

A Sarawak-based artist, Sonia Luhong Wan’s foray into the art world began early on in life with colourful scribbles on encyclopaedias, and she has never looked back since.