What does the Malay literary landscape look like? We speak to Hafiz Hamzah, co-founder and editor of the Svara journals, to discover what shapes the beauty of Malay literary writing today.

By Clara Ling

The earliest works of Malaysian literature were passed down orally in the absence of written scripts. Covering a variety of genres such as folklore, romance, myths, legends, epics, poetry, and proverbs, the storytelling tradition thrived among Malay communities, influenced by well-known Indian epics such as the Mahabharata and Ramayana. The introduction of Islam to the Peninsula during the fifteenth century brought about a shift. Scribes were hired to record significant events of the Malay sultanate and one well-known piece—written during the Malacca Sultanate, rewritten in 1536, and revised in 1612—is preserved as Sejarah Melayu (The Malay Annals). By the nineteenth century, oral Malay literature in the Peninsula had largely been replaced by written literature, leaving us with a vast treasury of literary works—including the various hikayats such as Hikayat Mara Karma, Hikayat Gul Bakawali, and Hikayat Panca Tanderan.

As a Universiti Malaya graduate in IT, Hafiz Hamzah has always been interested in reading and exploring the Malay literary scene. Malay literature places much emphasis on the function of the environment in life, reflecting the aesthetic beauty of human thinking, reasoning, and even the way human behaviour changes overtime. To Hafiz, co-founder and editor of Svara, it spells out a collection of life, customs, beliefs, and heritage.

Hafiz Hamzah, co-founder and editor of Svara. Photo courtesy of Hafiz Hamzah.

The shift beyond traditions

Over the years, the Malay writing scene has crafted its own authentic positioning in the literary landscape we see today. Moving on from hikayats, young writers who write in Malay today are slowly exploring different styles and aspects—avoiding status quos such as political concepts emphasising on Ketuanan Melayu (Malay pre-eminence). Reading preference has also changed: the general public usually opts for English writings instead of Malay ones. This factor could be due to the context in which the Malay language is being used by the media. Whatever people consume from news reports, social media, mainstream channels, and so on seem to portray the language as being outdated. In reality, Hafiz believes that “the Malay language can be widely explored and distorted to come out with creative ways of using it.”

There is also a stereotype that only Malays would read Malay literary writings—yet there is no doubt that Malay literature plays a crucial role in shaping the culture and inheritance of Malaysians. This became a driving factor for Hafiz to include more universal subjects in Svara.

“We should [write about] issues that cover more people and not just themes that cover only the Malay communities. I see the Malay literary scene playing a role in shaping the culture of Malaysians. It is not a one-night thing. As long as people read, as long as it moves forward, it will open our eyes and conscience towards important issues,” comments Hafiz. With the shift of lifestyle and perspectives, current issues discussed in Malay writings now include mental health, patriarchy, social media, and politics—topics that were not present in earlier works.

Three editions of Jurnal Svara published in 2021. Photos courtesy of Hafiz Hamzah.

The challenges and future of Malay literature

Hafiz specially notes that the worry now in the contemporary Malay literary writing scene is the shortage of long-form essays and novels—writings that people can dive into and raise arguments about or bring life to a situation. This has been a concern and is unhealthy for the Malay literary landscape. As Hafiz explains, most younger writers prefer to write shorter works due to the amount of time, research, and effort involved in longer writings. As many younger writers opt for poetry even over short stories, the general public must pay attention to the preservation of such weightier writings.

Younger writers are passionate about creating new ideas, exploring new styles of writing. There is quite a fair balance between male and female Malay writers. However, the challenge is whether these writers will continue to write. Where will they be in the next decade or so? As social media content fills up our news feed, people generally opt for more “fast food” news and writings, deteriorating the Malay literary scene which in return, causes Malay literary writing to become the least celebrated choice.

In light of this, Hafiz urges young writers to put their writing out there. “When you first start out, it may not be a popular choice, but down the road, maybe people will celebrate it. For me, if I’m writing, I’m doing it for myself. I don’t like the feeling of owing myself something. You cannot just dream of writing. Act it out. Writing is an action. No matter how bad it is. Do not show it on social media. Look for friends to read it, find out what they think. Be open to critiques. It is part of the learning process.”

Globalisation has brought forth free publishing mediums such as blogs and social media platforms and in Malaysia, the Malay writing scene is very encouraging for young writers. Young writers tend to opt for such free or self-publishing platforms due to the given freedom of content creation, development, and writing style—using these platforms as a stepping stone. Of itself, this is not entirely a concern, though Hafiz raises an important issue about the preservation of editorial quality, especially in contemporary Malay literature.

The significance of a publishing house must not be forgotten or neglected. When attached to a publishing house, the novice writer can be sure of obtaining proper criticism, quality guidelines, and writing feedback, with editors guiding writers towards improving their work. Although there is a limited number of independent Malay publishing houses, it is quite evident that these publishing houses are receiving very good response in recent years. As the Malay literary scene is still growing and taking shape, the more people are concerned about the quality of Malay writing, the more the Malay literary scene will keep maturing.

“One of the reasons why [we created] Svara is because when you print something, it will be there [physically]. You cannot play with it. You are giving it life. The discipline and concern behind it are different. It sticks with you and you can see your progress as you look back. If you publish [it for] free online, people can access [it]. But I don’t want people who access it to not appreciate the work. Therefore, the writer needs to decide,” advises Hafiz.

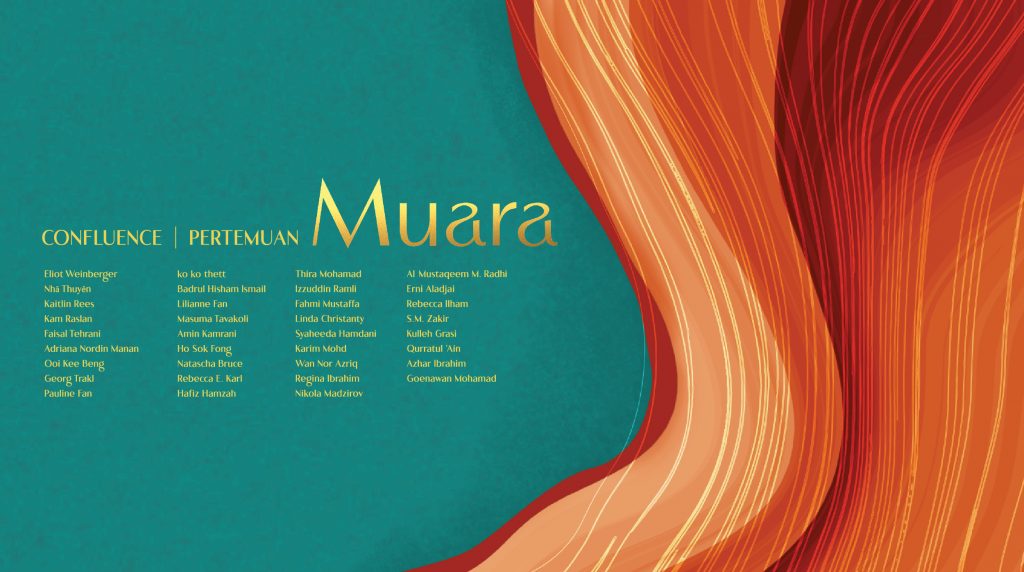

Featuring essays, lectures, short stories, poetry, book reviews, and translations, Muara gathers established and emerging writers from Malaysia, the region, and the world. This special publication produced in collaboration with George Town Literary Festival (GTLF) will be launched during GTLF 2021 to celebrate its 10th year. Photo courtesy of Hafiz Hamzah.

The importance of Malay literary writings must be discussed—it represents a big part of who we are as Malaysians. It is a collective living memory that provides a guideline for current generations and the generations to come. Malay literature is a storehouse of ideas on how we, as Malaysians, use this land to preserve our culture. Therefore, more than just preserving the language itself, the Malay literary landscape must be maintained and understood as repositories of cultural privileges that can be identified, experienced, and acknowledged. Sustainable efforts in encouraging younger writers to engage in Malay literary writings should be practiced and be a driving factor for the future development and advancement of Malaysia.

But more than a preservation of culture, Malay literature also moulds the way we live our lives. As Hafiz comments, “Literature shapes our imagination about life, about being Malaysian.”

Clara Ling is a writer by day and a creator by night. She has been involved in art writing, research, and publishing after finishing her Masters in Fine Arts.